For ten years I’ve been working on a viral disease of amphibians (and sometimes reptiles and fish) caused by ranaviruses. We’ve just published some new research showing how changes to the climate have been facilitating the spread of this disease and leading to some very serious outcomes for UK frogs. This blog post briefly covers the background to this important wildlife disease and the findings of this latest research.

THE PROBLEM:

- Ranavirus disease (ranavirosis) is a pretty nasty viral disease in frogs, typified by systemic haemorrhaging

- what that means is the frogs bleed throughout their bodies, something akin to what can be seen in the human disease caused by ebola virus.

- Diseased animals usually die.

- The disease is already widespread in England, where it kills the adult frogs, and has been shown to have caused population numbers to decline by more than 80% in ponds in south-east England within a decade.

FUNDAMENTAL FINDINGS: We showed that warmer temperatures help the virus grow and make it more virulent, more deadly if you like. In the wild, this has led to more frequent outbreaks of disease that each killed more frogs on average.

CLIMATE CHANGE: With respect to climate change, these were our key findings:

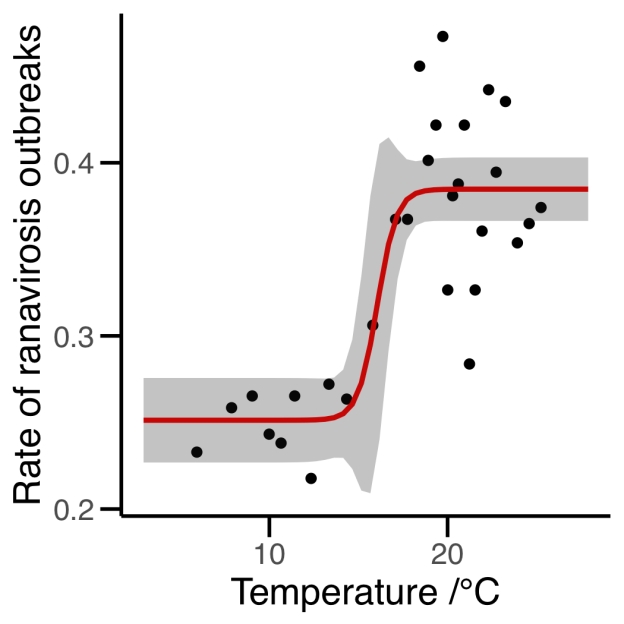

- Climate change has already had an impact on this disease. Looking at the last few decades, the rate of outbreaks tracked temperatures, so during warmer years there were more outbreaks of disease

- The things we’ve learned about what has already been happening give us a good basis to make predictions about how the future will unfold. When we did that we found a couple of things:

- One is that climate change will help the disease to spread and we can expect to see these big frog die-offs happening across more of the UK. The disease is already pretty widespread in England but will expand northwards and westwards, affecting frogs in more of England as well as Scotland and Wales

- The second thing is that the length of the disease season will increase. At the moment we mostly see disease during the warm summer months but going forwards conditions could become suitable for disease in April in the south of England. This is when tadpoles and froglets are still in the pond and would almost certainly mean we’d start to see them dying as well as the adults. If that meant that the adults that died were no longer replaced, then those frog populations could disappear almost overnight.

FROGS: And just to say what I mean by frogs here so that there’s no confusion. The species we’ve been studying is the common frog, which is the only frog that people commonly find in the UK. So when I’m talking about frogs disappearing, it’s not like it’s one type of frog and people will continue to see other types…we’re talking about ALL frogs.

A POSITIVE: This is all obviously pretty depressing and extremely worrying BUT some of our results hinted at possible mitigation measures. Where frogs had the means to stay cooler via shading or deep ponds, things weren’t so bad. It might be that if people start making their garden ponds more like a natural pond, with shading and a range of depths and dedicated to wildlife, instead of bowls full of fish (which can also make disease outcomes worse) surrounded by paving, we might give frogs a better chance of being able to tolerate infections.

TAKE HOME MESSAGES:

- People are generally pretty aware that the climate in the UK is changing and are probably used to headlines about the “hottest temperatures on record” and such, but this study shows how climate change has already impacted our wildlife and is changing the make up and appearance of our environment, even the animals we encounter in our back gardens. This situation is very likely to worsen.

- Although climate change has been a gradual process, the suggestion here is that the impacts won’t always be gradual. Predicting the future of complex ecological interactions is really difficult but we’ve been able to unpack some of the complexity in this system and it looks like the effect of climate change on this disease could reach a tipping point, which would mean that frogs disappear almost overnight in some places.

- Our study also shows a pretty indirect effect of climate change on wildlife and how climate change can act synergistically with other threats/factors, which can make it hard to predict the impacts.

BIG PICTURE: I think you can look beyond this study and generalise our findings. Science is just beginning to comprehend the astonishing amount of viral diversity that surrounds us, but has previously gone undescribed. Environmental change means that new threats to wildlife and human health will emerge that we don’t really have adequate means to predict.

You can find links to the complete research paper here

Citation: Price SJ, Leung WTM, Owen CJ, Puschendorf R, Sergeant C, Cunningham AA, Balloux F, Garner TWJ & RA Nichols (2019). Effects of historic and projected climate change on the range and impacts of an emerging wildlife disease. Global Change Biology. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14651